Description

Most recent AI binder design methods are structure-based and trained on the Protein Data Bank (PDB). This limits them to learning from a small, biased subset of proteins that are stable and crystallizable. Many therapeutically important targets, especially disordered, flexible, or viral proteins, are poorly represented in the PDB, meaning structure-based models often struggle or require heavy filtering to find a viable binder.

Here, we take a different approach: sequence-based binder design. Instead of using complex structures, we train on ~10M interactions from the STRING database, which captures a far broader and more diverse distribution of protein-protein interactions, including those that do not appear in the PDB. Our method, forge, uses latent flow matching, a state-of-the-art generative modeling technique, to perform target-to-binder generation directly from sequence. Given a target sequence, forge generates a corresponding binder sequence with no structural input required. (See our design method description for additional details.)

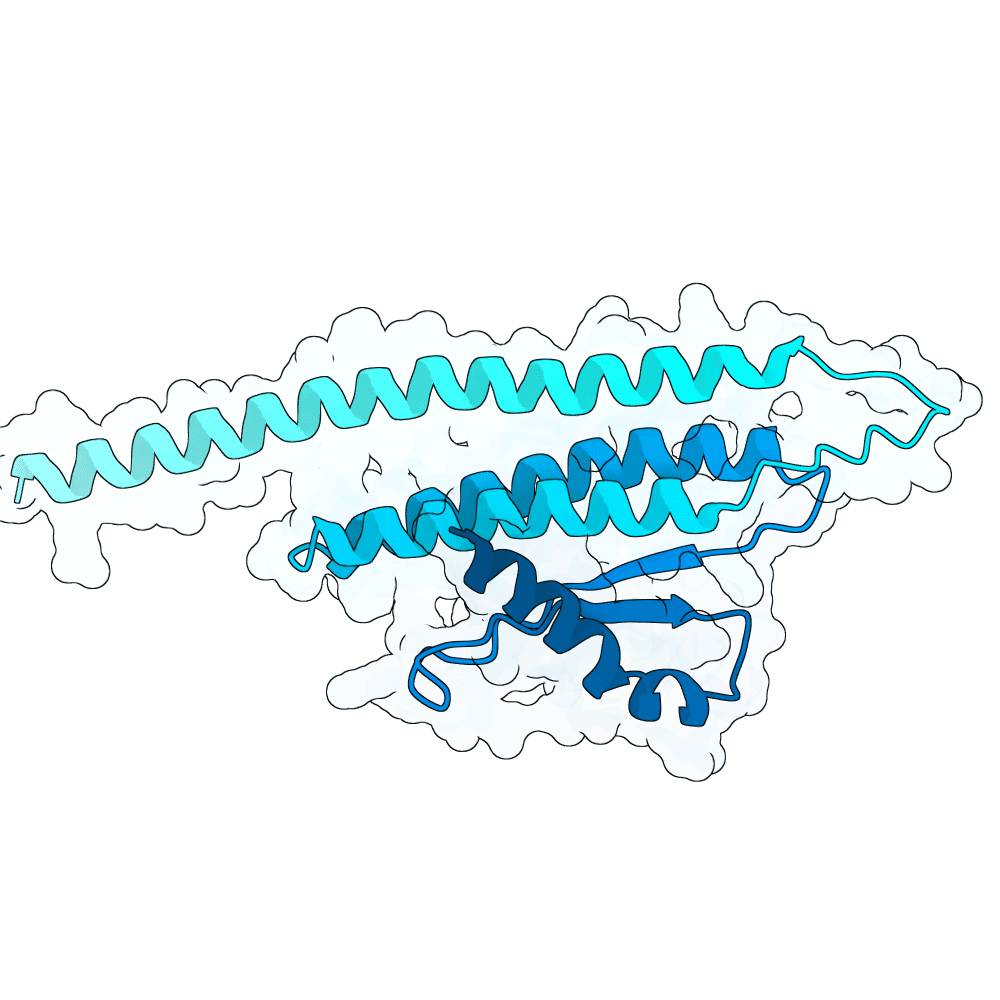

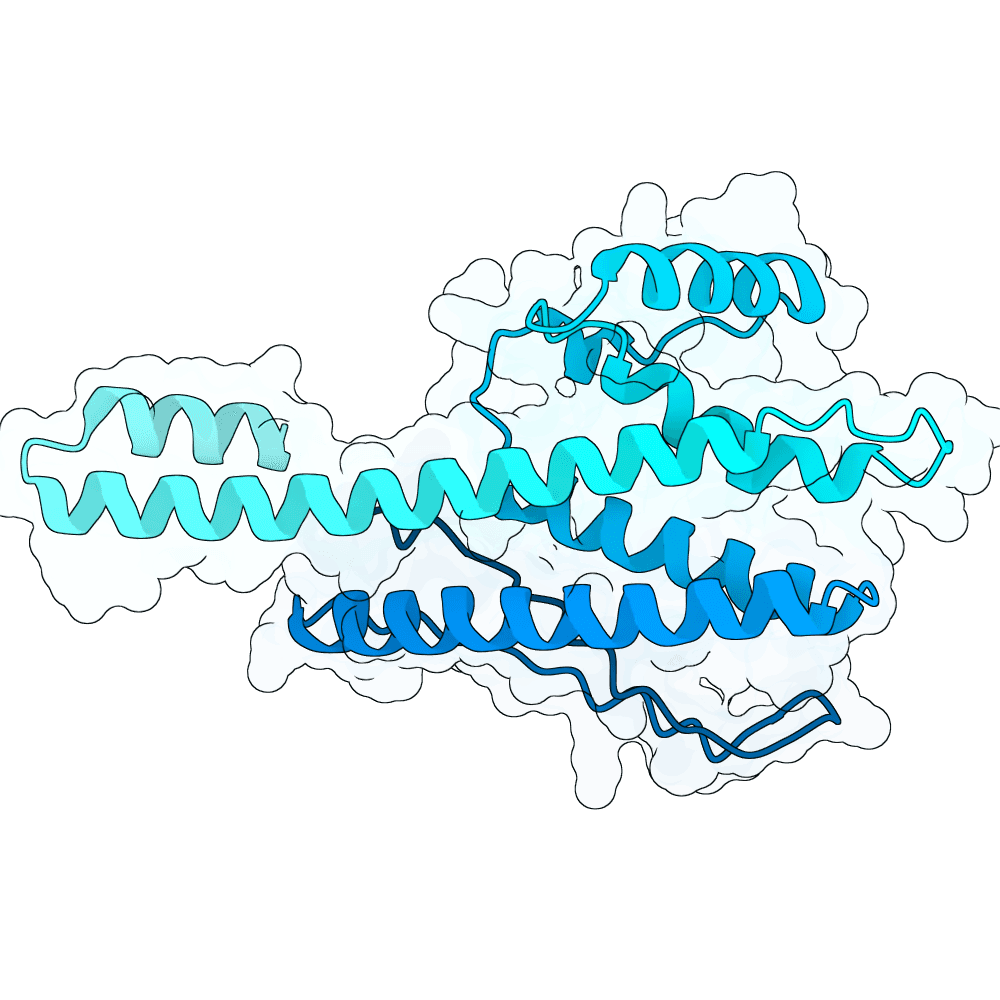

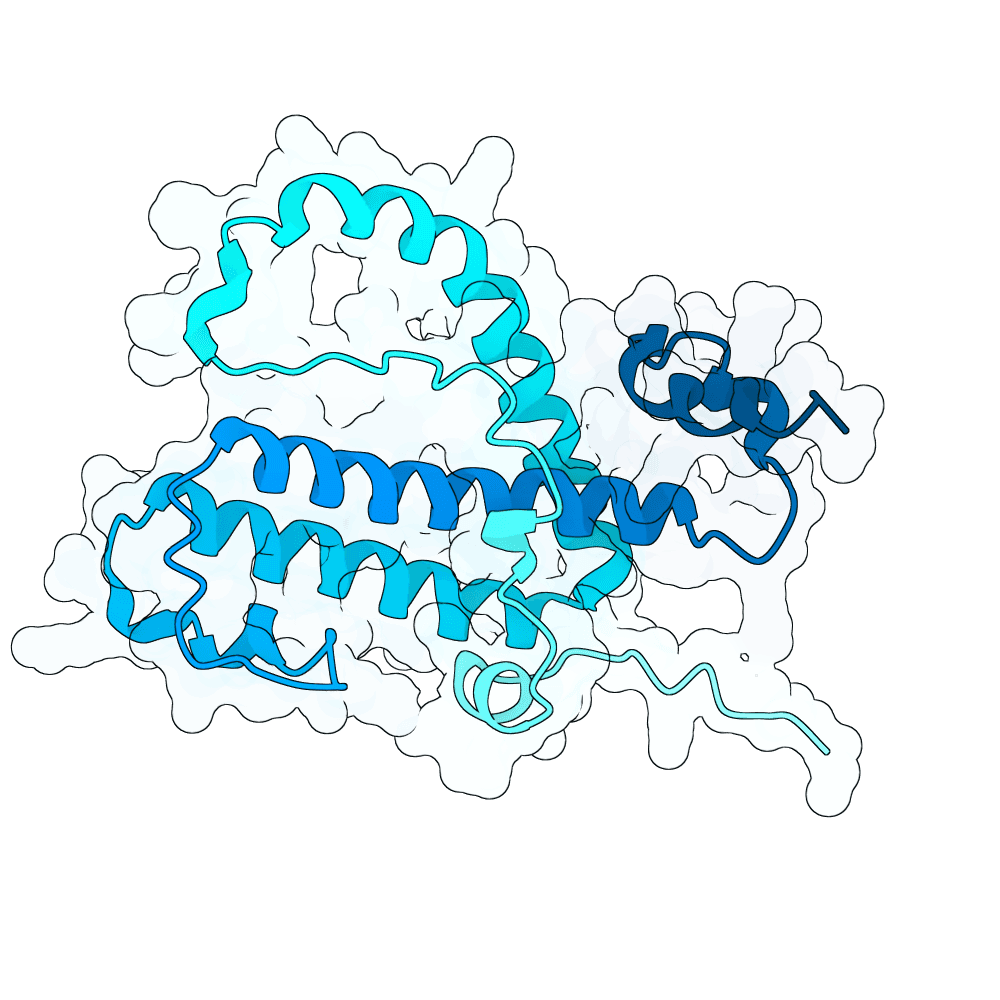

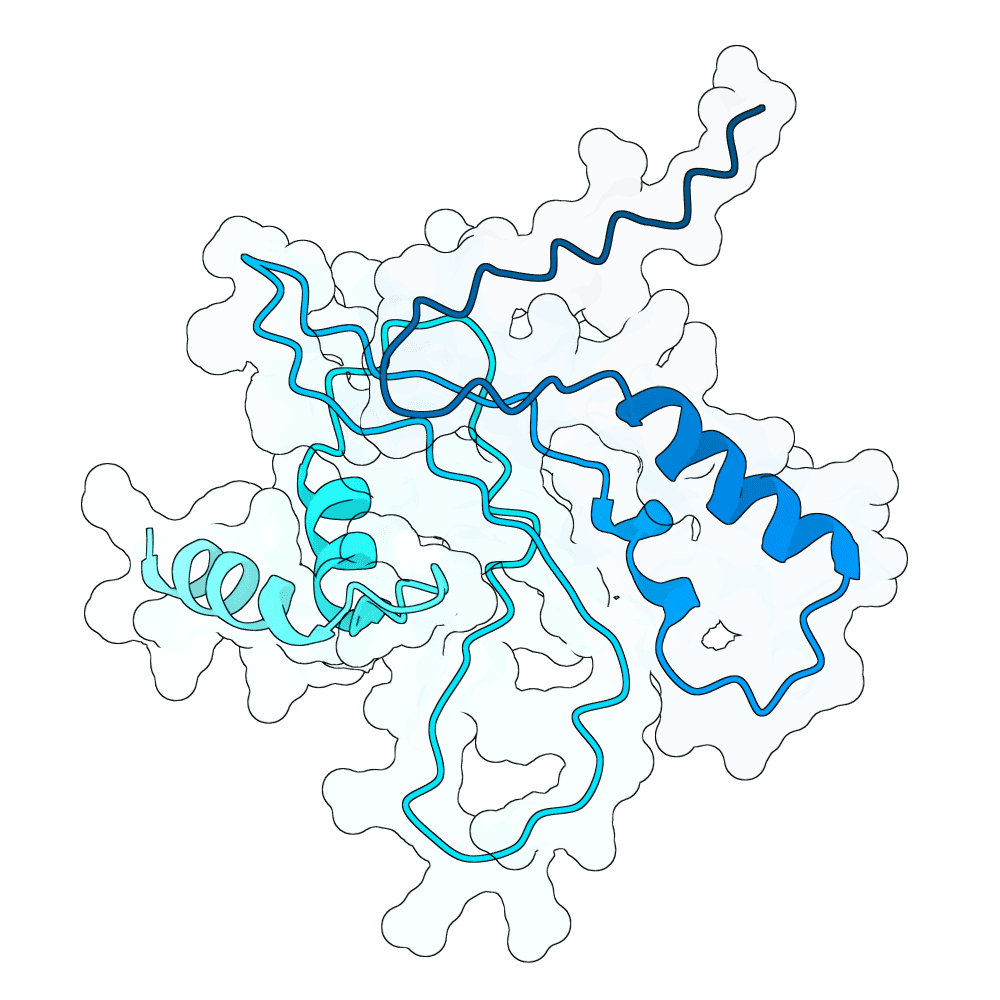

For this competition, we conditioned forge on the C-terminal region of the Nipah virus G protein and generated candidate binders between 100–250 amino acids. Now for the obvious question: why is the average ipSAE score so low for this submission?

One of the challenges of sequence-based binder design is that the current ecosystem for evaluating binder design structure-based. Think ipTM, ipSAE, etc., these all require the predicted binder-target structures to compute. But since forge is trained on STRING and learns from proteins never seen in the PDB, it can generate binders that are very un-PDB-like (many of our designs have <20% sequence identity to any PDB structure). This means the structure predictor (here, we use Boltz) may struggle to accurately predict the binder structure, leading to a poor in-silico metric.

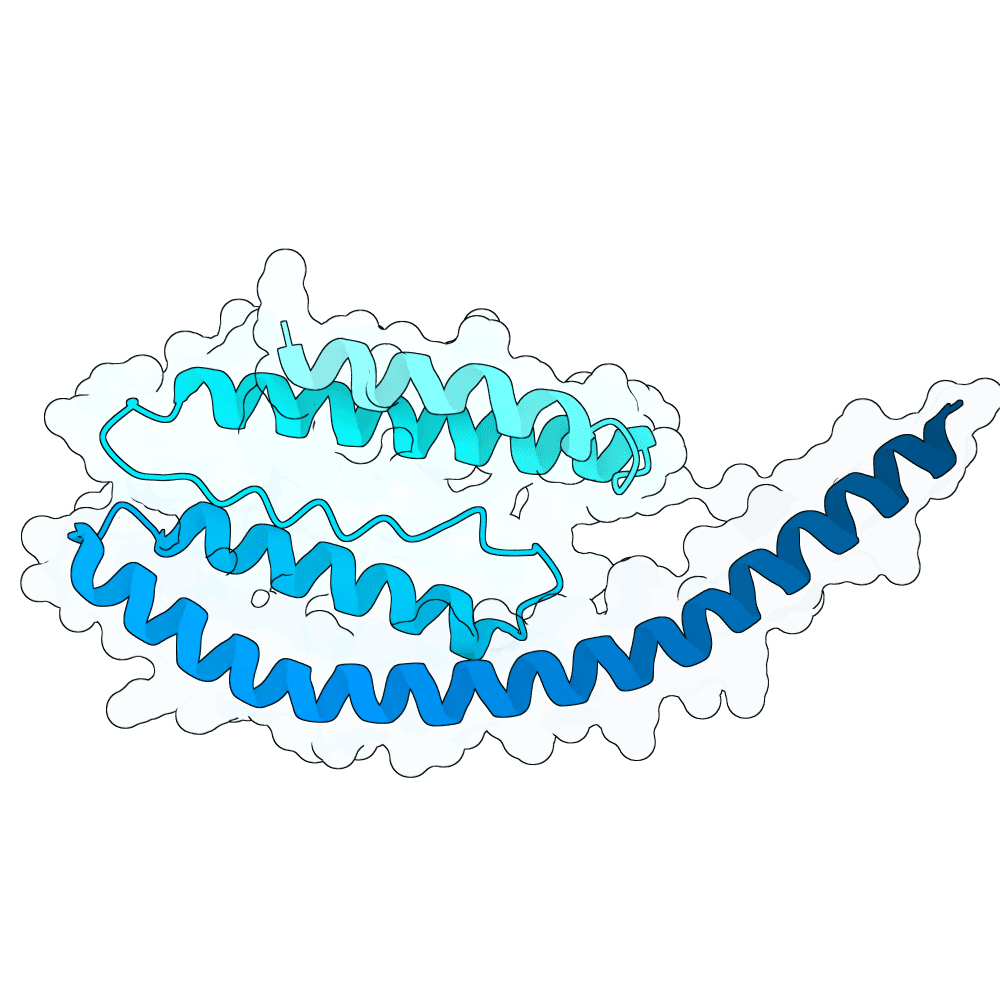

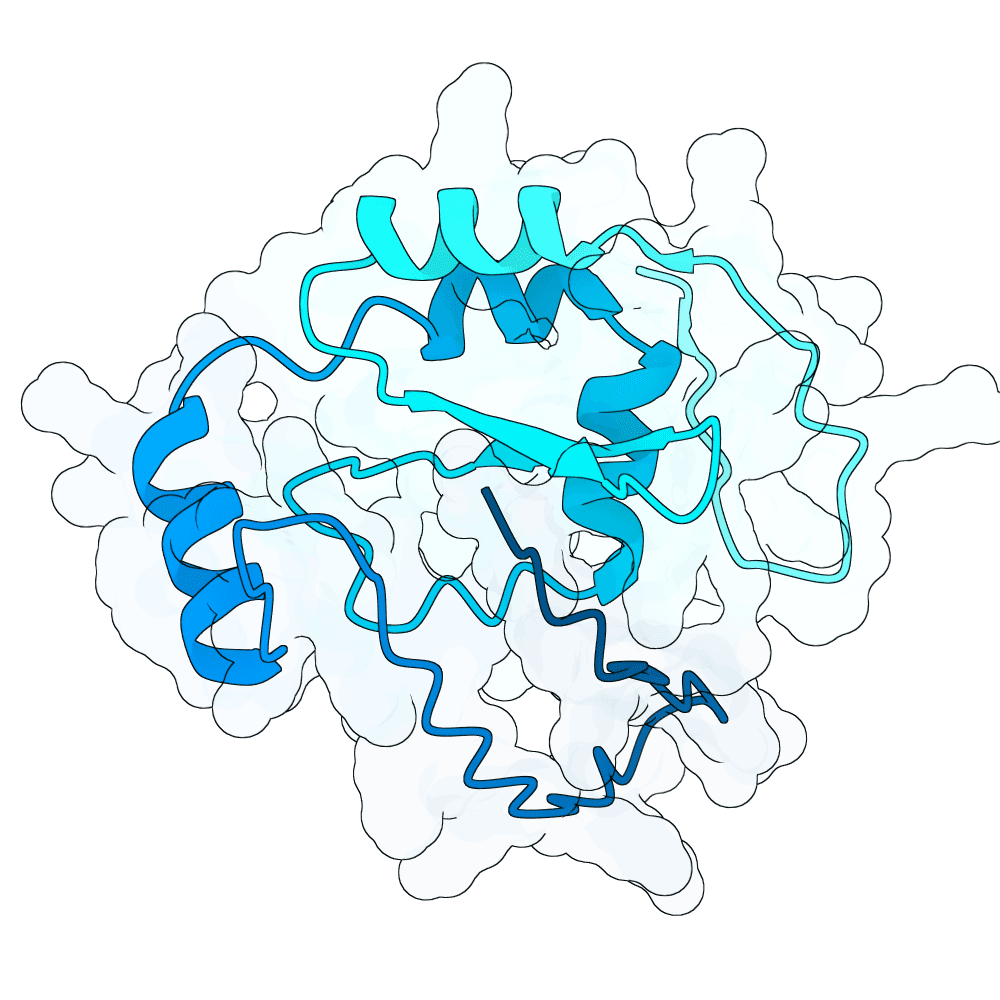

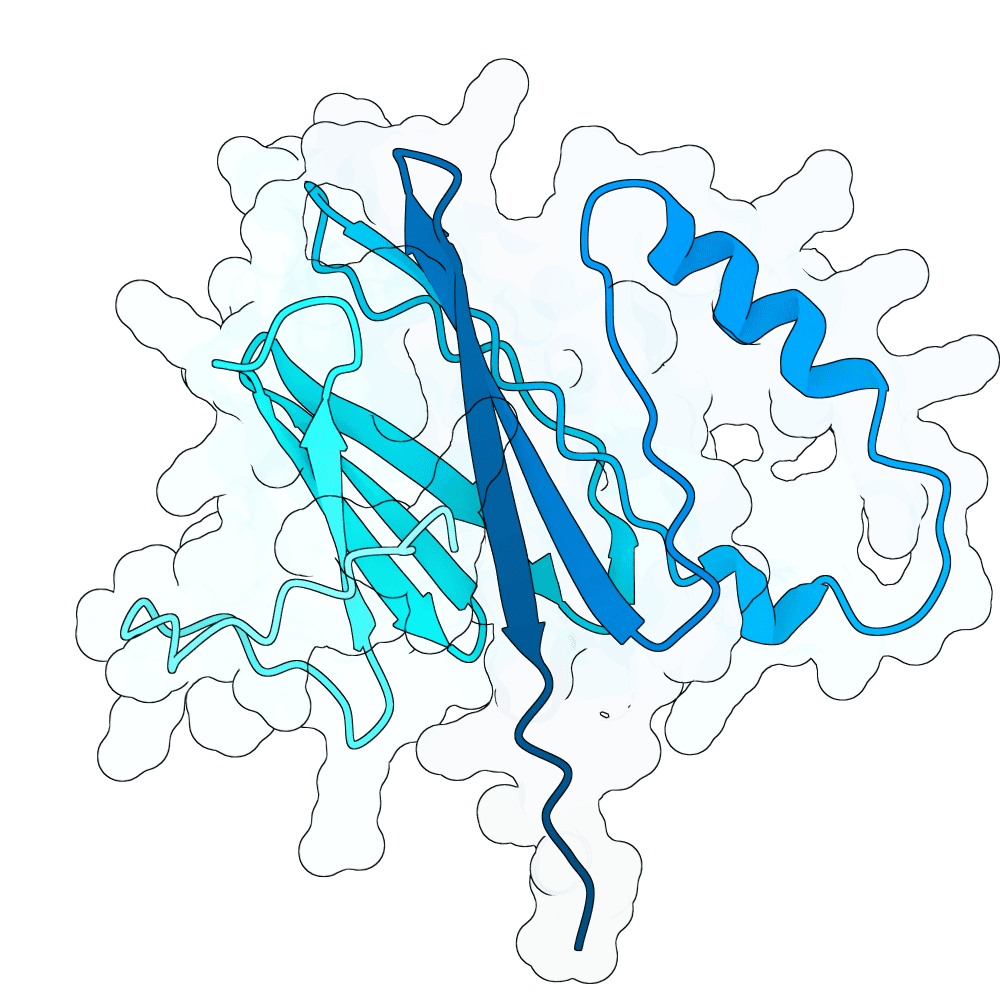

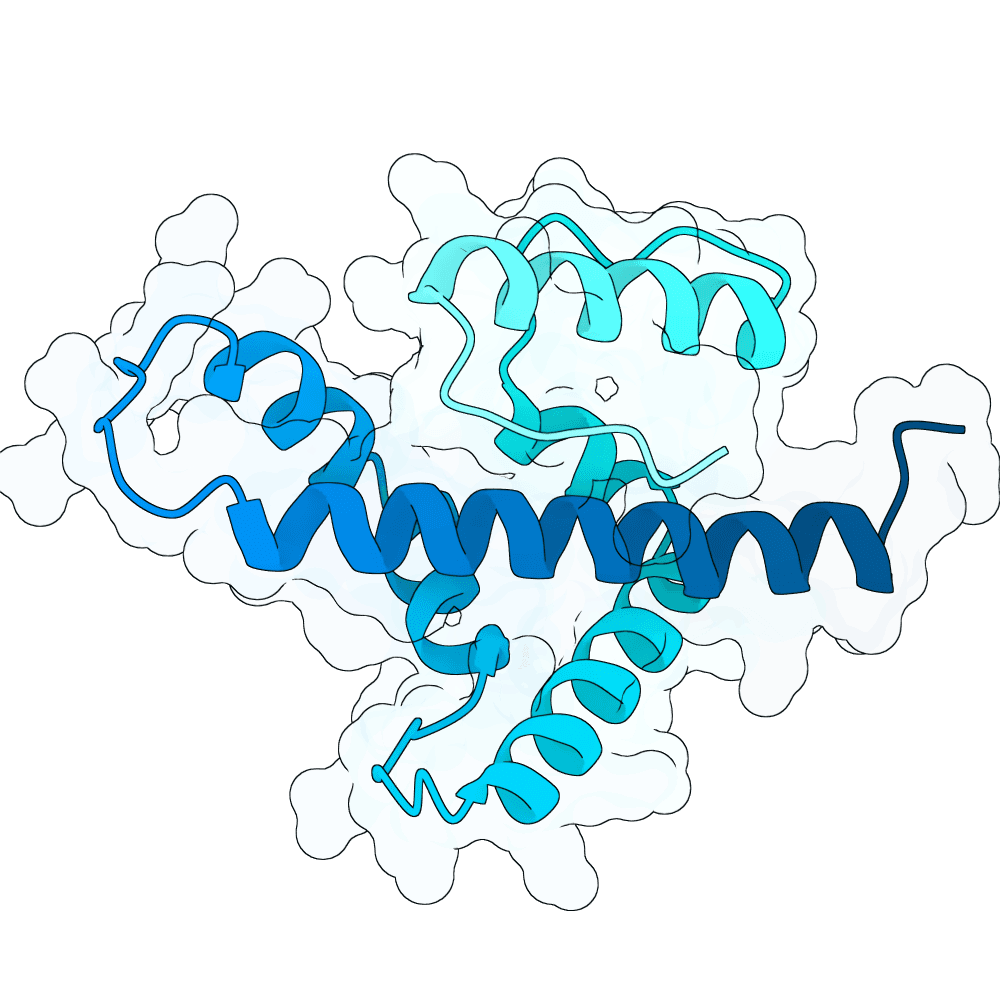

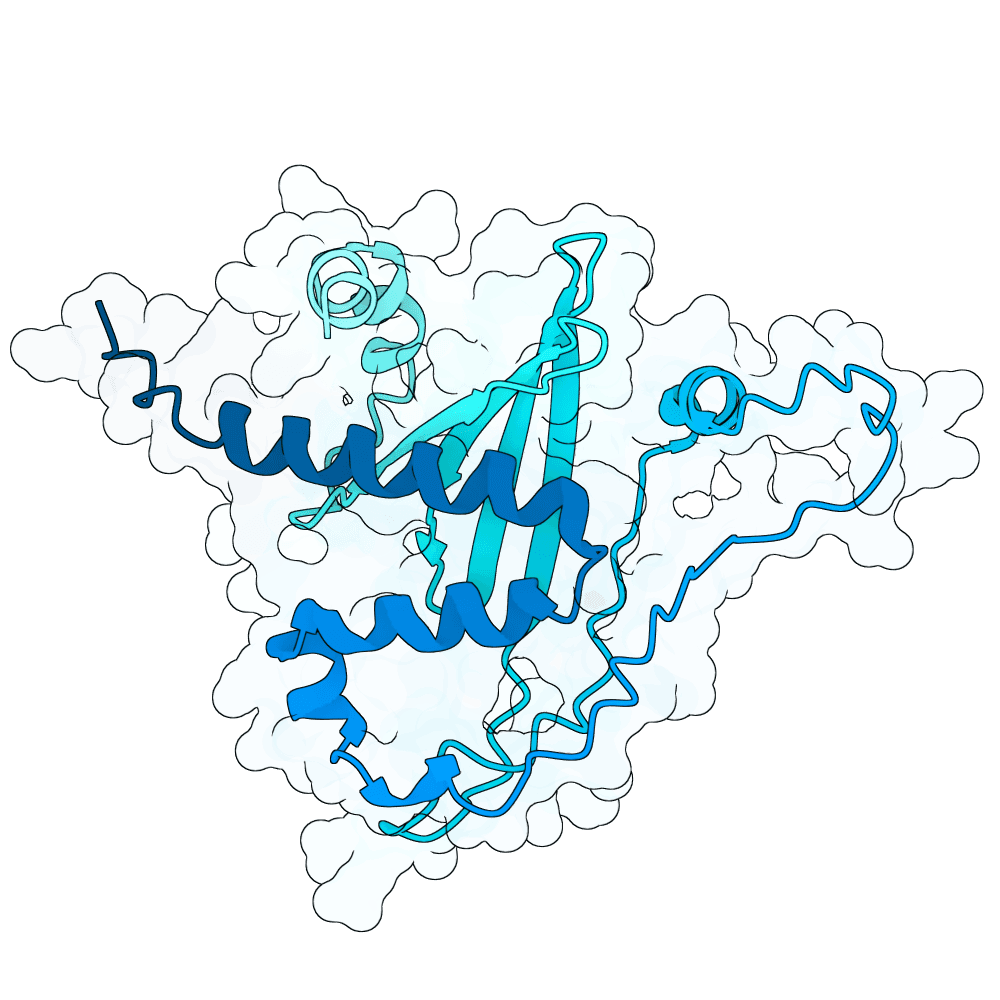

So, how did we choose the 10 sequences in our submission? Without a well-established evaluation infrastructure for sequence-based binders, this was challenging for us! While we initially went for the highest ipSAE scores, we realized we didn't want to rely too heavily on structure-based metrics. In the end, we selected five sequences with the highest ipSAE and five additional sequences with lower scores but predicted complex structures that place the binder at C-terminus. While adding additional filters could be useful, it adds confounding variables (does our model generate well vs does the filter select well). As we ultimately want to know how well our model generates true binders from the start, we decided on only using ipSAE for the competition.

In summary, deep learning methods are shaped by the data they learn from. forge embraces this idea by learning from a vastly richer and more natural interaction space than the PDB. Despite forge still being a work in progress, we believe sequence-based binder design has the potential to address the shortcomings of structure-based methods. Vote for forge if you want to see how far sequence-based design can go!